Bec's Story

-----------------------

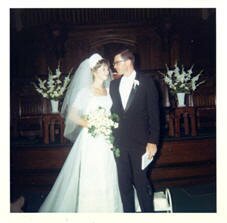

My husband George Edward Gilbert was born

in a little town in north central Pennsylvania

called Danville (it was an iron-mining town).

He was the oldest of five boys.

George was a really great big brother

to his brothers.

It was what made him prime

husband and father material, too.

He went to Juniata College for undergraduate school

(majored in physics and math).

The first in his family to do so,

and then he went to Temple University

in Philadelphia for graduate school,

which is kind of how we got together.

---------------------------

We were both teaching days in the suburbs

and going to school nights

for our Masters' degrees in

center city Philly.

It was really dangerous

(people would jump out from

between parked cars and mug you)

so we drove into the city together

and he would walk me to class

and then back to the car.

We didn't have time for food until

9:30 or 10 o'clock at night

and so we would stop for hamburger dinners

at a Shoney's Big Boy on the way home.

Talking to each other at Shoney's was

how we got to know and like each other.

His brothers and my kids wrote a eulogy

for him that I think captures who he was.

----------------------------

GEORGE'S EULOGY WRITTEN BY HIS FOUR

BROTHERS AND HIS CHILDREN

Memorial Service, April 2,2004

The family gathered and composed

this tribute to George

George is our hero.

We admire him as surely as

we admire George Washington,

Walt Disney, Franklin Roosevelt,

Martin Luther King, and Ghandi.

In this generation of our family

George is the person we admired

and tried to emulate.

No one will take his place.

He will remain the cherished head

of our family.

In the early years of television,

when George was growing up,

the cowboy wearing the white hat

was the role model.

George's favorite was Roy Rogers

Looking back we can see the

influence these cowboy models,

and others such as Superman,

had on his life.

George Gilbert would not have

chopped down the Cherry tree.

If he did, he too would have told the truth about it.

If someone needed to be rescued,

George rose to the occasion.

If a student at school needed extra help,

George provided it on his own time.

George never shot the person wearing the black hat;

he shot the gun out of his hand.

If you needed him, he was always there.

He was not the singing cowboy,

and he was not the modern day troubled cowboy.

He knew who he was.

He was very proud.

He was confident he could handle

whatever challenge he faced.

Yet, those who knew him understood

he was a loving and humble person.

He believed the famous quotation

"Pride is concerned with who is right.

Humility is concerned with what is right."

He avoided conflict by finding

practical solutions to the matters at hand.

George seldom had to draw his gun.

He was the small town Sheriff handling the

difficult jobs yet thrilled at the enjoyment

the job returned to him

George was happy that someone would pay him

for doing something he loved, teaching.

Even in the first grade George showed an aptitude for math.

One day the teacher asked all the students

to stand and count until they could go no further.

One by one the students reached their limits and sat down.

George was the last student standing.

He stopped only at the teacher's request.

He recalled, "I felt I could go on forever".

His gun remained firmly in his holster.

George was captain of the Danville High basketball team

and made the Southern All Star Team in his senior year.

His natural athletic ability

enabled him to participate in community sports

and to enjoy the camaraderie.

He played in the Council Rock Faculty Softball League,

he loved bowling and won Council Rock's

longest drive golf tournament.

Combining math and softball,

his uniform number was not a number,

but rather a formula:

Pi to the zero power, which equals the number one.

At Juniata College George earned the honor of residing in the

"Ranch", a suite of rooms in the Old Cloisters

reserved for the top eight senior students.

George's roommates were amazed by his photographic memory.

They liked to tell about the time George returned from a test

and was able to recall every question as well

as the multiple choice answers so everyone

could immediately determine their test performance.

----------------

George respected authority.

He was not a rebel.

You can't be a rebel when you

are wearing the Sheriff's badge.

He did not lash out when

an obstacle barred his path.

He followed a thoughtful and logical path.

He analyzed the situation and used his intellect

to devise a solution all parties found acceptable.

He was Marshall Matt Dillon, hearing gunshots,

calmly walking to the troubled scene, and handling it.

The outcome would be the one that was right,

the one that was supposed to happen.

There was no doubt or surprise ending.

The right person was behind bars and the person

who was hurt was gently being assisted

and returned to their happy family.

------------------

George met Becky while taking classes

at Temple University.

He escorted Becky to class through dangerous neighborhoods.

Early in their relationship George told her he was going to marry her.

He wore his white hat, drew his gun and got his girl.

Towards the end when George's

chemotherapy treatment caused his fingers to swell,

he could no longer wear his wedding ring.

To signify their endless love he asked that his ring be fused together

with Becky's to form an infinity sign.

George raised Sandy and Duff the old-fashioned way -

doing what a parent should do,

protecting and loving them,

leading them by example, having fun,

being with them, teaching them independence,

and supporting their decisions.

to build their confidence and self-esteem.

A man of action rather than words,

George showed them love by

spending his time contributing to their interests.

He not only attended their basketball games,

he was actively involved in helping them improve

their jump shots or their defensive strategy.

To amuse and educate them, he would rise before dawn

on weekends to prowl through flea markets

in search of games/ toys/ tools

and memorabilia that fit their interests.

We will miss him and we will

look for him when we need him.

He will be there for us because

he is part of us and inside of us.

As we go through life wearing our deputy badges,

we will treat others as he did.

We can't expect to rise to the same level as our hero,

but we don't need to. We have George.

We won't say goodbye because he is still here.

------------------

A DEATH IN THE FAMILY

by Becky

I couldn't cry for myself when I lost

my husband because I knew

(from psychology classes in my past)

that tears were the evidence of plain old self-pity,

and since George was dying no matter

what we tried to do to prevent that,

I couldn't pity myself:

he was the one who was being

so brave and suffering the loss of all he held dear.

Doctors had told us right out of the gate

that his illness was terminal,

that there was no cure, that he was going to die from it,

probably within six months to a year of diagnosis.

Lots of couples before us had faced the loss of each other

and of their way of life,

but when it's you looking down the barrel of the cannon,

you do some pretty dumb things, I guess.

When we got the news, we went into hiding.

It was as if we thought we could ignore the facts

if we didn't examine them too closely.

We told only immediate family,

because we knew from the year before,

when George had had prostate cancer surgery,

that there would be lots of questions.

We didn't want to answer them,

just wanted to eat dinners together in our den

and hang out in a little glow-y island of peace

Never mind that the glow was us burning our bridges.

---------------

After two weeks, George's brother Jack

who managed a Radiology practice in Charlotte, NC,

and whom we had told "because he might know something,"

gave us what for and it sank in that if we did nothing,

there was no chance to prove the doctors wrong.

We naively thought that maybe if we fought like Jack said,

there was a chance we might be "the ones" (who beat the disease).

At least, in the meantime,

we'd have had us the best medical advice there was.

It was time to fight back, we agreed,

even if the odds were 99.9% against us.

"None but the brave deserve the fair" (John Dryden).

I think we left off the denial phase at this juncture

and slipped into "Fight the dragon on all sides with whatever is handy,

even if it's only a knife and fork."

We discovered that there were few forks and only butter knives,

but we had begun, finally, to fight.

-------------------

Though George was an agnostic and I was a remodeled atheist,

I believe we both did some bargaining with a God or the gods

to plead for more time/a whiz-doctor/

something to believe in besides doom and gloom.

My prayers were basically,"If You'll.... then I'll..."

I felt that Mercy had looked the other way as had Justice and Love.

We hooked up, though, to an online cancer site called ACOR

and with a really savvy medical ombudsman named Joanne Goldberg

and dug into research, which is how we "got a grip"

and also heard about the leading doctors in mesothelioma treatment:

David Sugarbaker at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston,

Valerie Rusch at Sloan-Kettering in New York City,

and Hedy Kindler at the University of Chicago in Illinois.

We began our Doctor-Odyssey in our black 94 Camry,

which I renamed "The Pennsylvania Rocket"

as we burnt up the Mass Turnpike,

the Pennsylvania Turnpike and The New York Thruway

in our search for someone who might perform

the delicate surgery that seemed George's best chance.

It was called an Extra-Pleural-Pneumonectomy, or EPP.

Someone would have to take out George's right lung,

the lining of his chest,

his heart sac and his diaphragm,

replacing everything but the lung with Gore-tex,

the stuff they use to make the outer shell of ski jackets

because it is waterproof and light

------------------

Since David Sugarbaker decided to take us on,

saying he would also give George a

"heated chemo wash" while he had him open,

we decided that maybe that was our best

(though scary) shot for a good result.

On the appointed day, Sandy and Duff and I sat for over eleven hours

in a crowded lobby at Brigham and Women's,

because the hospital was under construction

and there was no place for families to wait.

There was also no real communication until about 4 pm

(they had started before 7 am)

when someone found us in the lobby to say George was alive

and doing satisfactorily (finally!),

that they were giving him the chemo wash.

Thank God for Sandy and Duff's company because they kept saying,

"The longer the operation goes, the better the news."

Whether they were right or not, it was good to have them there.

A little island of family in a strange hospital in a strange town

is a small campfire in the wilderness of primitive feelings.

Next day, we dubbed George's shared room (a ward) "Hocker Heaven"

because nurses would go from bed to bed

pounding on patients' backs to clear their lungs

and make them cough up mucous so they'd stay clear.

George was in incredible pain even

with the wire of his spinal infusion sticking out of his back.

A rib that had been removed was giving him fits

and he looked sicker than a starving dog.

My job was to bug nurses for anything he needed and

to keep him company when he was lucid.

It was probably then that we divided our roles into

Brave Non-Complainer and Cheerleader/Step-n-Fetchit.

I had a small Notebook Computer we had bought at a flea market

and I would take it back to my motel room every night

and keep everybody in both our families and in Council Rock

up-to-date on what was happening with him.

The next day, I would take messages to him

(that I had to copy longhand because I had no printer)

and read them aloud to him.

----------------------

It was a hard time for both of us

because I lived in a hospital-owned motel for a month

(it had better rates but wasn't a well-oiled machine),

getting up early to get to the hospital in time for rounds

(sometimes I actually made it and got to see Dr. Sugarbaker

if I took a taxi and if the taxi was prompt)

and I stayed until closing,

and then had to take a bus or taxi back to the motel

(there was no such thing as parking at the hospital)

and then I wrote e-mails until I dropped.

George, of course, had it worse,

but he always was glad to see me

and always let me know that whatever I did for him was appreciated.

He surprised me by never taking me for granted.

He never assumed (like I would have)

that the world revolved around him just

because he was going through an ordeal.

When I saw how humble he was,

I was ashamed of myself for all the times I had been tough on him

instead of recognizing what a gem he was and letting him know that.

----------------------

One really hot day, when he fell asleep,

I left his room and went outside to the street

to look up an ice cream store I had seen that looked promising.

I bought myself a cone and stood in the sun licking it

and feeling guilty that I could walk and stand in the sun

with a simple cone while George was trapped indoors

fighting to recover from a harsh operation.

It was like I could feel the beginning of a divide between us

a rift that had never been there in our thirty-eight years of marriage

one that had been forced on us because we had no choice

if we wanted him to have a chance.

I went back to his room to try to close the rift and rubbed his feet

(which was the only thing that took

his mind off his other pains for a few minutes)

and told him about the hot sun, the cone

and the things going on in the street so he

wouldn't miss out on them altogether.

After that month of recovery, there were a couple weeks

when the hospital let me take him to the motel I was living in

to see how he'd fare "in the world"

before they gave me permission to take him home (in the PA Rocket).

I found that the motel would let me have a little

refrigerator and a hot plate,

things that I'd really need because George couldn't go to a restaurant

(discomfort and infection risk)

and so we camped out in the room together,

exercising his legs in the hallways and dining on soup and franks

and other one-pot meals until they said we could go home.

Though he got a minor infection after two weeks at home

and I had to take him back to Boston feverish and lethargic,

he was still plenty game post-surgery and had lots of fight.

-----------------------

George got better before he got worse again.

When he was better, we lived almost normally

except that we lived for "Pulse-Ox" readings.

(A pulse-oximeter is a hinged device that clips onto an index finger

and registers blood-oxygen level and pulse rate.)

The higher the oxygen level in his blood,

the better George could breathe and

endure things like visits from company.

When the Pulse-Ox was low, he mostly sat and slept

(easier than lying down with his missing rib).

We began to talk about things like "treading water"

(waiting until the lifeboat of Help came along,

help like Emend for chemo nausea and Alimta,

the new meso-chemo),

about how you balance a checkbook

(I had no system; he'd always done the balancing),

about where the insurance policies were

and how much they were worth, etc.

In other words, he began educating me - the heretofore "ditz"

about all the things I'd need to know to survive.

He showed me how to figure out our income taxes

according to his system - and luckily he did,

because I would have been totally scared out of my mind

when the IRS decided to audit our taxes from the year 2002

two months after George died in 2004,

claiming I owed them a LOT of money in "back taxes and fines."

George was such a good teacher that I knew

there would be an understandable explanation.

The figure the IRS said we hadn't reported was an oddly specific one which,

in my desperate search for "what George would do"

I found in our 2002 tax return;

It had been reported, just was on the wrong line.

After many phone calls and letters,

they said I only owed a fine for late payment

and they let me off the "back taxes" rap.

It wouldn't have happened if George hadn't been sick and sinking in 2002

but I could feel him looking over my shoulder telling me to

"look again at the 2002 return for that specific number."

-------------------

The trips to the hospitals (ones closer to home as the end neared)

were for things like massive blood clots,

suspected pulmonary embolisms,

putting in and removing a "port" and IV's of various kinds.

Lots of non-meso things were starting to go wrong.

We always went together for every treatment.

We always believed that "where there is life, there is hope."

We were one person with two bodies if that is possible.

United in purpose.

I wrote most of a dopey novel called

Wanton Wiletta and the Pussyfoot Cafe

on my lap in waiting rooms and hospital rooms

when George dozed and there was nothing else I could do for him.

When I was at home, I typed up the notes I had

written on paper cribbed from nurses,

on the backs of place mats and tray-liners

from hospital cafeterias,

on pages from the backs of notebooks

in which I kept records of every visit we made

to every doctor we had ever spoken to

and what we asked and what the answers were.

I kept trying to organize all the paper

and I think it kept me from losing my sense of humor by cultivating one.

There was a mountain of stuff to keep and maintain!

The book kept me patient and the notebooks

kept me sane and on top of things.

Being on top, however,

didn't prevent the disease from running its course.

-----------------------

A major step down was the decision to go with an air compressor 24/7.

It stayed in our living room but had a long enough hose that,

for a while, George could sleep in our bedroom upstairs

if I walked behind him and uncoiled hose as we went up

and recoiled it again as we were going downstairs,

but it wasn't long before the stairs

were too much for him and I couldn't lift or carry him,

I would have been injured along with him if he fell.

It was a real blow when the oncologist suggested hospice.

Neither of us believed the doctor meant NOW.

I think we were angry that he was "rushing things,"

When you've been fighting for four years for something you want,

you lose sight of changes that are obvious

to those with more objectivity.

We maintained our schedule of chemo:

George took a chemo treatment the week before he died,

though he had to be taken there

as he had for appointments of all kinds for some time,

in a wheel chair with an oxygen tank on the chair.

The word "Hospice" meant "giving up" to us

because it was explained that you promise

you will not seek medical treatment in a hospital.

Because George gave everything careful thought

and took his time making decisions

(never let himself be rushed or talked

into acting on a whim like I did/do),

he didn't tell me to call hospice until he must have already

decided he could go no further, that he was worn out.

I didn't want him to give up and, at first,

refused to call hospice for him (he was bed-ridden)

but we finally struck an agreement.

I would call hospice for him if I didn't have to sign any papers

indicating my agreement with his decision.

Like a mule, I wouldn't give ground,

felt no sense that the end was near.

Hospice said over the phone that the morphine they were going to send

would be there the next day and that they would visit then.

-----------------------------

That night, when I was giving George his evening pills,

instead of swallowing them with water,

he crunched them up noisily in his teeth like carrots.

I thought he was joking around until he slid back onto the mattress

and fell into a deep sleep without responding to my questions.

It was an unnatural sleep.

I called hospice and described what had happened.

----------------------

The nurse on duty told me to start using the liquid morphine

Fox Chase had given me and put a dropper full inside his cheek

where it would absorb quickly into his bloodstream.

I did

I was to repeat it every hour.

I did, but looking back on it,

I'm pretty sure it was the wrong thing to do.

George wasn't in any greater pain than usual that night

and the frequent morphine was not something his body was used to.

At eleven-thirty pm, George suddenly jumped up out of bed

though he'd been unable to even sit up by himself for some time.

He leaped into a standing position on the floor yelling,

"Unhh!, Unhh!, Noooo!, Noooo!"

He was looking out of the room and right through me,

couldn't focus and was frightened out of his mind.

I don't know how I held onto him in his agitation

because he had more strength at that moment than he'd had for months.

-------------------------

"It's okay, George," I told him over and over,

"I'm here and everything's okay,"

but he went on looking terrified and saying,

"NOO! NOOO!"

I could tell he was "seeing something"

hallucinating and that I wasn't there with him in the nightmare.

When I was sure I couldn't hold him anymore,

he suddenly collapsed back onto the bed.

I called hospice and they said to call someone to stay with me,

that it could happen again and to keep giving George the morphine.

I called my son though he was in bed

and told him hospice told me to get help.

He came right away and got the bed rails out of the garage.

We surrounded George with pillows

so he couldn't hurt himself if he tried to jump up

and hit the rails,

but he never moved after that

and I continued to give him the morphine

the hospice said to administer

because I was afraid to think for myself,

given what had just happened.

Duff and I talked about whether to call Sandy and what to say.

We decided that since this might be "It",

that George was dying, we had better call her.

We didn't know whether she could make it home in time

to talk to her father while he was still alive,

and we knew that people in a coma

have come back to say they could hear

what had been going on around them.

so we held the phone to his ear and let her talk

for as long as she wanted.

Finally, she told us she was going to try to find a flight home

to be with her father.

She got home at noon and George suddenly sat up,

sighed, and died at 2:20pm that afternoon.

-----------------------

My husband died at home where he wanted to be,

in the den which was "his" room more than anyone else's.

It was where he always had graded papers

and watched (or listened to) television while he worked.

It was the heart of the house for him,

just as the kitchen was the heart of the house for me.

And he was gone.

Just like that.

To ask God for him back would have been the most selfish thing

I could do since I had watched him slowly

and grudgingly give up his grip on life

which he loved more than any other person I have ever known,

enjoyed every minute of that life,

even the hard parts, and still had to throw in the towel.

Giving up was a decision he made only

when the constant grind of pain got to be too much for him,

and the giving up cost him his belief that

"Good guys win." He knew he was a good guy who, through no fault of his own,

was not going to win this time.

He lost his battle with mesothelioma,

an asbestos-caused terminal cancer on March 26th, 2004.

He was only sixty-one years old and should have been able

to look forward to "ripening on the vine of old age"

instead of withering away before the eyes of all the people who loved him.

----------------------------

----------------------------

I remember the day, less than a month before he died,

when I got angry as hell in a supermarket

because I couldn't deny anymore that he was dying.

I was standing in Genuardi's in the bread aisle.

During the fifteen minutes I'd allowed myself to pick

up groceries and get back to him.

And there in the bread aisle was a bent,

white-haired couple who must have been in their eighties,

discussing which loaf of bread to buy.

What made me so mad was that I felt cheated.

George and I would never have the chance

to stand together and make a weighty decision

about bread while the rest of the world walked around us.

George, who had called this same store from his

hospital bed in our den to order 38 red roses

for me that Valentine's Day

"one for every trip around the sun we had made together"

was out of time,

and so was I.

----------------------

Who do you complain to when you feel you've been

cheated out of the hand that reaches for yours?

It was God's plan that this should happen.

I couldn't see why God would plan this

"Death in the Family" for a while,

but I know now that I had some

"new lessons in living"

to learn.

Things like I could cope with the IRS

and not "skate" through life being so dependent on another

and George

needed out because

he was just plain tired

and I was never going to agree with that.

In the five years he has been gone,

I have made peace with God,

but I still miss George and always will.

There was only ever one of him and now he is gone.

--------------------

The thing about George's meso

is that it may have been from more than one source.

Lawyers interviewed him in depth

and took most of the stuff he had collected and used

from our basement and garage.

What they found out was that George had done

brake work on our cars and that many of the cans

and boxes in our basement and garage

had asbestos in them.

There was even asbestos

(which was removed, after his death,

from the classroom ceiling and the hallway

in the school building where he had worked for so many years).

He wouldn't consider suing the school district

because that would have been spitting on the school district

he had loved,

but the lawyers pursued manufacturers of products he had used

puttering and repairing things around our home.

They were sure that any one of the asbestos-containing products

could have been the cause of his meso

and they were the experts.

We were not.

We bowed to their judgement

because they had been through this fact-finding

before and we had not.

--------------------

Whether George's mesothelioma

came from one cause or ten, we couldn't be sure

but what we knew for certain

was that George enjoyed living,

would not have given up the opportunity

to see his grandson Kyle grow up,

wrote in shaky handwriting

(since he was by then so sick)

a letter with a "first car" payment

in it because he knew he wouldn't

be able to be there himself

to give it to this grandchild he loved

(Kyle was six months old when George died)

and surely he wouldn't have missed meeting his

granddaughter Lauren,

who would have stolen his heart

(she's five today, was born three years after his death)

------------------------

What is family worth to a family man like George?

Everything.

Because of asbestos,

our grandchildren will have no real concept

of how funny and

wonderful their missing Grandpop

would have been,

the games he would have invented for them.

Even his students remember his math problems

disguised as chicken jokes.

The humor was never the lesson

for the young people he loved to share this planet with,

but I know George lightened hearts with his

"Attaboy!/ Attagirl!!"

spirit and his sense of fun.

------------------

The main thing about George

after his love of life,

is that he was a guy who always looked forward.

He didn't sit around asking himself,

"Why me?"

but was the kind of man who would say,

"Why not me?"

and do his best to face whatever

was confronting him.

Whether it was his humility or his bravery

in the face of a fearful diagnosis

that explains why he didn't dissolve in self pity,

I can't say,

but I still look to him as the one true love of my life

who was and is irreplaceable.

He is my Shining Example of how to go on.

------------------------

On To Janelle's Story